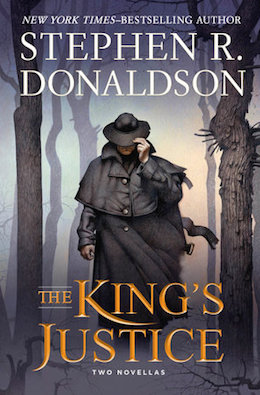

The King’s Justice collects two new, original novellas—Stephen R. Donaldson’s first publication since finishing the Thomas Covenant series—are a sure cause for celebration among his many fans. Available October 13th from G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

In the title story “The King’s Justice,” a stranger dressed in black arrives in the village of Settle’s Crossways, following the scent of a terrible crime. He even calls himself “Black,” though almost certainly that is not his name. The people of the village discover that they have a surprising urge to cooperate with this stranger, though the desire of inhabitants of quiet villages to cooperate with strangers is not common in their land, or most lands. But this gift will not save him as he discovers the nature of the evil concealed in Settle’s Crossways.

The “Augur’s Gambit” is a daring plan created by Mayhew Gordian, Hieronomer to the Queen of Indemnie, a plan to save his Queen and his country. Gordian is a reader of entrails. In the bodies of chickens, lambs, piglets, and one stillborn infant he sees the same message: the island nation of Indemnie is doomed. But even in the face of certain destruction a man may fight, and the Hieronomer is utterly loyal to his beautiful Queen—and to her only daughter. The “Augur’s Gambit” is his mad attempt to save a kingdom.

THE KING’S JUSTICE

The man rides his horse along the old road through the forest in a rain as heavy as a damask curtain—a rain that makes dusk of midafternoon. The downpour, windless, strikes him from the long slash of open sky that the road cuts through the trees. It makes a sound like a waterfall among the leaves and branches, a damp roar that deafens him to the slap of his mount’s hooves. Ahead it blinds him to the road’s future. But he is not concerned. He knows where he is going. The broad brim of his leather hat and the oiled canvas of his cloak spare him from the worst of the wet, and in any case he has ridden in more frightening weather, less natural elements. His purpose is clear.

Shrouded by the deluge and covered by his dark gear, he looks as black as the coming night—a look that suits him, though he does not think about such things. Having come so far on this journey, and on many others, he hardly thinks at all as he rides. Brigands are no threat to him, even cutthroats desperate enough to hunt in this rain. Only his destination matters, but even that does not require thought. It will not until he reaches it.

Still his look does suit him. Black is the only name to which he answers. Many years ago, in a distant region of the kingdom, he had a name. His few comrades from that time—all dead now—knew him as Coriolus Blackened. But he has left that name behind, along with other pieces of who he once was. Now he is simply Black. Even his title rarely intrudes on who he has become, though it defines him.

He and his drenched horse are on this road because it leads to a town—so he has been told—called Settle’s Crossways. But he would have taken the same road for the same purpose without knowing the name of the place. If Settle’s Crossways had been a village, or a hamlet, or even a solitary inn rather than a town, he would still have ridden toward it, though it lies deep in the forests that form the northern border of the kingdom. He can smell what he seeks from any distance. Also the town is a place where roads and intentions come together. Such things are enough to set and keep him on his mount despite the pounding rain and the gloom under the trees.

He is Black. Long ago, he made himself, or was shaped, into a man who belongs in darkness. Now no night scares him, and no nightmare. Only his purpose has that power. He pursues it so that one day it will lose its sting.

A vain hope, as he knows well. But that, too, does not occupy his thoughts. That, too, he will not think about until he reaches his destination. And when he does think about it, he will ignore himself. His purpose does not care that he wants it to end.

The road has been long to his horse, though not to Black, who does not protract it with worry or grief. He is patient. He knows that the road will end, as all roads must. Destinations have that effect. They rule journeys in much the same way that they rule him. He will arrive when he arrives. That is enough.

Eventually the rain begins to dwindle, withdrawing its curtains. Now he can see that the forest on both sides has also begun to pull back. Here trees have been cut for their wood, and also to clear land for fields. This does not surprise him, though he does not expect a town named Settle’s Crossways to be a farming community. People want open spaces, and prosperous people want wider vistas than the kingdom’s poor do.

The prosperous, Black has observed, also attend more to religion. Though they know their gods do not answer prayer, they give honor because they hope that worship will foster their prosperity. In contrast, the poor have neither time nor energy to spare for gods that pay no heed. The poor are not inclined to worship. They are consumed by their privations.

This Black does think about. He distrusts religions and worship. Unanswered prayers breed dissatisfaction, even among those who have no obvious cause to resent their lives. In turn, their dissatisfactions encourage men and women who yearn to be shaped in the image of their preferred god. Such folk confuse and complicate Black’s purpose.

So he watches more closely as his horse trudges between fields toward the outbuildings of the town. The rain has become a light drizzle, allowing him to see farther. Though dusk is falling instead of rain, he is able to make out the ponderous cone of a solitary mountain, nameless to him, that stands above the horizon of trees in the east. From the mountain’s throat arises a distinct fume that holds its shape in the still air until it is obscured by the darkening sky. Without wind, he cannot smell the fume, but he has no reason to think that its odor pertains to the scent which guides him here. His purpose draws him to people, not to details of terrain. People take actions, some of which he opposes. Like rivers and forests, mountains do not.

Still he regards the peak until the town draws his attention by beginning to light its lamps—candles and lanterns in the windows of dwellings, larger lanterns welcoming folk to the entrances of shops, stables, taverns, inns. Also there are oil-fed lamps at intervals along his road where it becomes a street. This tells Black that Settle’s Crossways is indeed prosperous. Its stables, chandlers, milliners, feed lots, and general stores continue to invite custom as dusk deepens. Its life is not overburdened by destitution.

Prosperous, Black observes, and recently wary. The town is neither walled nor gated, as it would be if it were accustomed to defend itself. But among the outbuildings stands a guardhouse, and he sees three men on duty, one walking back and forth across the street, one watching at the open door of the guardhouse, one visible through a window. Their presence tells Black that Settle’s Crossways is now anxious despite its habit of welcome.

Seeing him, the two guards outside summon the third, then position themselves to block the road. When the three are ready, they show their weapons, a short sword gleaming with newness in the lamplight, a crossbow obtained in trade from a kingdom far to the west, and a sturdy pitchfork with honed tines. The guards watch Black suspiciously as he approaches, but their suspicion is only in part because he is a stranger who comes at dusk. They are also suspicious of themselves because they are unfamiliar with the use of weapons. Two are tradesmen, one a farmer, and their task sits uncomfortably on their shoulders.

As he nears them, Black slows his horse’s plod. Before he is challenged, he dismounts. Sure of his beast, he drops the reins and walks toward the guards, a relaxed amble that threatens no one. He is thinking now, but his thoughts are hidden by the still-dripping brim of his hat and the darkness of his eyes.

“Hold a moment, stranger,” says the tradesman with the sword. He speaks without committing himself to friendliness or animosity. “We are cautious with men we do not know.”

He has it in mind to suggest that the stranger find refuge in the forest for the night. He wants the man who looks like a shadow of himself to leave the town alone until he can be seen by clear daylight. But Black speaks first.

“At a crossroads?” he inquires. His voice is rusty with disuse, but it does not imply iron. It suggests silk. “A prosperous crossroads, where caravans and wagons from distant places must be common? Surely strangers pass this way often. Why have you become cautious?”

As he speaks, Black rubs casually at his left forearm with two fingers.

For reasons that the tradesman cannot name, he lowers his sword. He finds himself looking at his companions for guidance. But they are awkward in their unaccustomed role. They shift their feet and do not prompt their spokesman.

Black sees this. He waits.

After a moment, the sworded guard rallies. “We have a need for the King’s Justice,” he explains, troubled by the sensation that this is not what he had intended to say, “but it is slow in coming. Until it comes, we must be wary.”

Then the farmer says, “The King’s Justice is always slow.” He is angry at the necessity of his post. “What is the use of it, when it comes too late?”

More smoothly now, Black admits, “I know what you mean. I have often felt the same myself.” Glancing at each of the guards in turn, he asks, “What do you require to grant passage? I crave a flagon of ale, a hot meal, and a comfortable bed. I will offer whatever reassurance you seek.”

The farmer’s anger carries him. Thinking himself cunning, he demands, “Where are you from, stranger?”

“From?” muses Black. “Many places, all distant.” The truth will not serve his purpose. “But most recently?” He names the last village through which he passed.

The farmer pursues his challenge, squinting to disguise his cleverness. “Will they vouch for you there?”

Black smiles, which does not comfort the guards. “I am not forgotten easily.”

Still the farmer asks, “And how many days have you ridden to reach us?” He knows the distance.

Black does not. He counts destinations, not days in the saddle. Yet he says without hesitation, “Seven.”

The farmer feels that he is pouncing. “You are slow, stranger. It is a journey of five days at most. Less in friendly weather.”

Rubbing at his forearm again, Black indicates his mount with a nod. The animal slumps where it stands, legs splayed with weariness. “You see my horse. I do not spur it. It is too old for speed.”

The farmer frowns. The stranger’s answer perplexes him, though he does not know why. Last year, he made the same journey in five days easily himself, and he does not own a horse. Yet he feels a desire to accept what he hears.

For the first time, the tradesman with the crossbow speaks. “That is clear enough,” he tells his comrades. “He was not here. We watch for a bloody ruffian, a vile cutthroat, not a well-spoken man on an old horse.”

The other guards scowl. They do not know why their companion speaks as he does. He does not know himself. But they find no fault with his words.

When the sworded man’s thoughts clear, he declares, “Then tell us your name, stranger, and be welcome.”

“I am called Black,” Black replies with the ease of long experience. “It is the only name I have.”

Still confused, the guards ponder a moment longer. Then the farmer and the man with the crossbow stand aside. Reclaiming the reins of his horse, Black swings himself into the saddle. As he rides past the guards, he touches the brim of his hat in a salute to the man with the sword.

By his standards, he enters Settle’s Crossways without difficulty.

In his nose is the scent of an obscene murder.

Excerpted from The King’s Justice: Two Novellas, by Stephen R. Donaldson by arrangement with G.P. Putnam’s Sons, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, Copyright © 2015 by Stephen R. Donaldson.